[Editor’s Note: The following is written by Mr. Perkins and shared with his consent]

After working 8 years in the manufacturing industry, in 1972 I became disabled due to exposure to welding fumes and airborne pollutants, causing me to undergo 3 weeks of treatment at Salem (Mass.) Hospital. After that, I found myself becoming increasingly allergic to tobacco smoke. I began to experience reactions causing various degrees of anaphylactic shock, disabling me on the spot, and making it difficult to find and hold down a job and buy necessities for life.

After working 8 years in the manufacturing industry, in 1972 I became disabled due to exposure to welding fumes and airborne pollutants, causing me to undergo 3 weeks of treatment at Salem (Mass.) Hospital. After that, I found myself becoming increasingly allergic to tobacco smoke. I began to experience reactions causing various degrees of anaphylactic shock, disabling me on the spot, and making it difficult to find and hold down a job and buy necessities for life.

People were smoking everywhere I went, which made my lungs feel like someone had poured gasoline into them and then thrown a match down after it.

I started attending meetings with Fresh Air for Nonsmokers, but their focus was on establishing nonsmoking sections, and not banning smoking in public places.

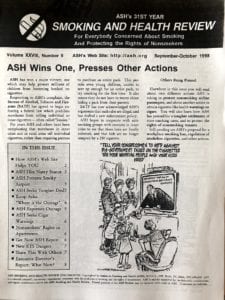

I found Action on Smoking and Health, and signed up with them, probably in the seventies. I also joined up with GASP, Americans for Non-Smokers Rights, Doctors Ought to Care, Stop Teenage Addiction to Tobacco, and others. These groups all sent me excellent bulletins which gave me a good education for non-smokers’ rights activism.

In 1977, I discovered the book, “The Legal Rights of Nonsmokers,” by two prominent attorneys, Alvin and Betty Brody, containing the wealth of information I was looking for. The book listed 16 of the most dangerous compounds found in tobacco smoke. I gave the list to Andy Pace, a former DuPont chemist, and asked him to give me an analysis; I found out for sure these toxins were harmful to all parts of the human body.

In 1989, I found the book, “The Passionate Non-Smokers’ Bill of Rights,” by Steve Allen and Bill Adler, Jr. The education I got from these books was priceless.

In 1989, I found the book, “The Passionate Non-Smokers’ Bill of Rights,” by Steve Allen and Bill Adler, Jr. The education I got from these books was priceless.

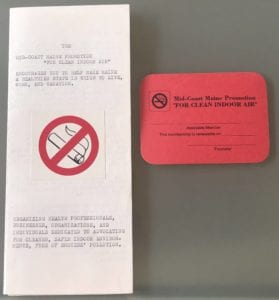

In 1980, I established the Mid Coast Maine Promotion for Clean Indoor Air. I tracked down people who had anti-smoking letters in newspapers, put them on my mailing list, and sent them a membership card. I had been working 8 hours a day at the YMCA in Damariscotta, Maine, so my activism took place 4-6 hours at night, and weekends, writing letters to editors, because that was the best way I had to reach large groups of people. I composed bulletins and copied others, and mailed them out to my members, legislators, churches, and other groups. My expenses ran from $400 – $700/year, mostly for copying and postage.

One year with two members of Boston GASP, we picketed a tobacco promotion in Augusta. We have attended a few Lung Association meetings in Augusta too.

One of our first activism concentrations focused on stopping the smoking in a Camden rest home, which was achieved. At the time, it was alleged that employees were feeding handicapped patients with one hand, while holding a lit cigarette in the other.

Several years ago, I submitted a bill to the legislators to make the legal age to buy tobacco products rise from 18 to 21, but it was rejected. A similar bill was introduced by someone else recently and it was adopted.

Since it became illegal here to smoke in all public buildings, I only rarely run into tobacco smoke. When that was achieved, my membership dropped to zero soon after. But that was not the end of the problems caused by tobacco use. Tobacco shops sprung up all over the state; although everything I tried to do to prevent that was ineffective. Now, we are having to deal with the promotion of “recreational” marijuana which causes problems similar to those cause by tobacco use. Lately I have been distributing anti-marijuana literature.

I still maintain my association with Action on Smoking and Health.

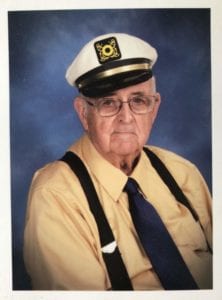

Ray Perkins

After thought: my slogans appearing on my bulletins and envelopes were “Tobacco smoke kills” and “Tobacco: America’s most widespread drug and pollution problem”.